Now that we have done a bunch of reading on personal finance, are paying ourselves first, have established our savings goals, and put some automation in place it is time to think about investing.

LBYM

I have mention lifestyle creep a few times, but it is worth restating – if you want to achieve personal financial success, or even Financial Independence, you must have the discipline to Live Below Your Means (LBYM.)

I believe many people confuse what it means to be wealthy with having a large income. While a large income certainly will help you attain wealth, no amount of income will make you wealthy if you stay on the hedonic treadmill our consumerist society is built to keep you on, and you keep spending more as you make more.

Wealth consists not in having great possessions, but in having few wants.

Epictetus

I can’t say it better than Epictetus. If our goal is to create wealth, then we need to focus equally on our careers and opportunities to make more money AND also keep our lifestyle in check. Then use the difference between income and expense to 1) pay down debt 2) build an emergency fund and set money aside for savings goals, and 3) invest.

We can see below the dramatic difference in the size of the investment portfolio you would need to achieve financial independence based on a given annual expense level using the 25x Rule.

| Annual Expenses | Investment Portfolio Needed |

| $50,000 | $1,250,000 |

| $60,000 | $1,500,000 |

| $75,000 | $1,875,000 |

| $100,000 | $2,500,000 |

| $150,000 | $3,750,000 |

Even if your goal isn’t financial independence or to retire early, being aware of lifestyle inflation and ensuring you live below your means will give you the fuel to fund your investment portfolio and give you the peace of mind that comes with not being overstretched financially.

Start (and stick with) index funds

The financial services industry has all manner of fancy products and big marketing budgets to get you to give them your money to manage. But despite what seems like common sense – that smart money managers backed up by teams of analysts (or AI powered ‘robo-advisers’) must be able to beat the market – it’s just not true. (Note: I’ll be referring to mutual funds in this post, and while they are different, you can also invest in ETFs. My points are true for both.)

Index funds are going to be your best bet for 3 main reasons:

Index funds outperform actively managed funds year after year

There are plenty of opinions as to why this is, but set that aside for the moment. The simple fact is that being invested in the entire market (or a substantial portion of it), which is what an index mutual fund buys you, beats actively managed funds year after year.

According to the SPIVA scorecard, for the 5 years ending December 2020, 75.27% of US Large Cap funds underperformed the S&P 500. That’s a lot of funds controlling a lot of other people’s money, with teams of (highly paid) analysts and money managers failing to beat an automated index.

Of course it does mean that 24.73% of funds did manage to beat the S&P 500. The issue with this is threefold:

- You have to pick the right funds, and while they definitely offer more diversification that picking stocks yourself, you have to do the research and somehow pick the right funds

- But it doesn’t stop there – just as with stocks, active funds go up and down, and fall in and out of favor. So you need to keep monitoring your funds and try to accurately decide when to sell, and what to buy to replace that fund in your portfolio. Fine enough if you enjoy it, but few people can accurately time the market or individual funds and stocks. Most humans are fundamentally inept at this and lose money in the market when they try to time things.

- What’s worse, actively managed funds are expensive, though deceptively so because of the way costs are articulated. So your actively managed funds not only need to beat the market, they need to beat it by more than enough to offset the likely thousands of dollars in extra fees you will pay, which we’ll look at next.

Actively managed funds are 10-20 times as expensive as index funds

When I started investing in the 1990s it wasn’t unusual to see mutual funds with expenses over 1%. Now that doesn’t seem like much right? I could even hear myself saying that was cheap – “one percent is worth paying for the 10% return.” The problem is that compounding works both ways, we all love earning compound interest, but mutual funds (and other financial products) fees also compound.

As a simple example, let’s look at a $10,000 investment that we let grow for 30 years (not unreasonable for a retirement account) at an 8% growth rate and a 1% annual fee. Using this CalcXML calculator we get:

It appears that your initial investment of $10,000 is estimated to grow to $74,434 reflecting opportunity cost and expenses totaling $26,193.

The way that $26,193 breaks down is $10,056 paid directly in fees and, this is where the compounding comes in, $16,137 opportunity costs – all the growth that we didn’t get from the money we paid in fees. Our lost earnings end up costing us more than the fees themselves, and we used an 8% growth assumptions, historically the stock market has returned 10%.

Now let’s look at a Total Stock Market index fund, both the Schwab1 and Vanguard Total Stock Market funds have net expense ratios of 0.03% as of this post. That not 3%, that’s 3/100ths of a percent, so that’s $3 per year on our hypothetical $10,000 investment versus $100 per year at 1%. So let’s see what that gives us:

It appears that your initial investment of $10,000 is estimated to grow to $99,725 reflecting opportunity cost and expenses totaling $902.

The way that $902 breaks down is $365 paid directly in fees and, this is where the compounding comes in, $537 opportunity costs.

So if you had invested in our actively managed fund in the first example, you might have been really happy to end up with $74,434. You might even think you’d been pretty smart to pick it, but would you feel that way if you realized that you gave away $25,291 to your fund manager? Even if they had out performed the market in a few years, they’d have to have really outperformed it to make up for the fees. And remember you pay these fees whether you are up or down in the market, so the fund company can’t lose. Now, in part thanks to pressure from index funds, active funds fees have been dropping, according to Morningstar “The asset-weighted average expense ratio for active funds fell to 0.66% in 2019 from 0.68% in 2018”, even using that number we still get opportunity cost and expenses totaling $18,130.

And as pointed our above they usually don’t outperform the market, so you end up actually paying a lot more money for poor performance.

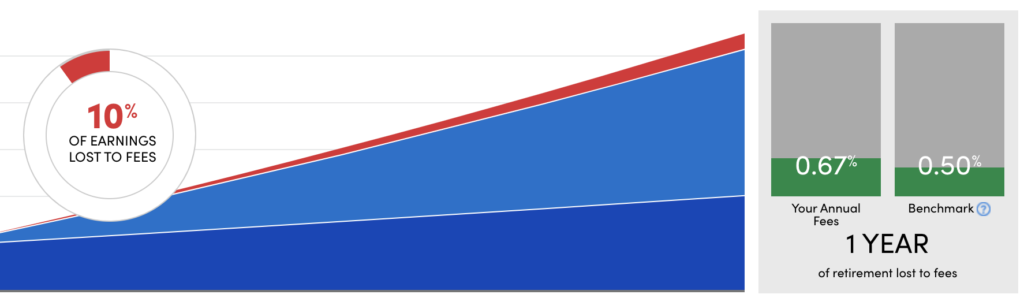

Personal Capital has an interesting view on this with their Retirement Fee Analyzer which shows how a seemingly ‘low’ fee of 0.67% results in 10% of lost growth opportunity over a 10 year timeframe on my existing retirement portfolio.

If you are worried at all about funding your retirement, fees should scare the crap out of you. I have managed my own fees down to 0.07% (mainly because I do have some money in international and emerging market index funds, otherwise it would be lower.) If you don’t know what you are paying in fees, you should stop reading this and go figure that out 😉

You can’t pick stocks (neither can I)

Stock picking is a fools errand, and even smart money managers backed up by a team will struggle to match the markets performance as detailed above. Why do you think you can do any better? No seriously, before you make a bet like this sit down and think through whether you have the time, the knowledge, access to the same information as professional money managers, the discipline, and the interest to keep up with it.

I learned my lesson early during the ragging dot-com bubble of the late 90s, back when we all thought we were brilliant for buying this dot com or that start-up. Many of my peers were getting in on IPOs, bragging about our gains, and thinking we were all going to retire in a year or two. (We were in our late 20s/early 30s, what the hell did we know.)

Then reality set in and market collapsed. I was invested in multiple technology focused funds, or a dozen individual stocks, lots of options and shares of my company stock, and fortunately a few Schwab and Vanguard index funds. I got wiped out to the tune of around an $800k loss, on paper at least. The technology mutual funds didn’t just drop, the fund companies themselves went out of business. The stocks I owned dropped a ton or simply went out of business, and the options I had were suddenly underwater to the tune of $50 or even $100 per share, most never to recover their value.

I mourned that loss for a good year; shock, anger, depression, resignation – I went through it all. But now from the vantage point of my 50 year old self I am glad it happened early in my investing career. I learned that I was not a brilliant stock picker, and I didn’t have the time to keep up with individual stocks. As I tallied my losses and unwound any remaining individual stocks I had, I put the remaining money in index funds, and kept putting money there.

We’re seeing this today in meme-STONKs and in the crypto market (I am not anti-crypto, but it is early days and it isn’t investing, so it belongs outside of your portfolio as speculation IMO.)

If you want to consistently and reliably build real wealth, with a simple portfolio that you can manage with a few hours a year and avoid panic selling or hype buying, you really can’t do better than a small set of index funds that you steadily invest in.

* I am not a financial professional or consultant, none of this information should be taken as advice for your specific financial and personal situation. Do your own research and form a plan that is appropriate for you.

1 Full disclosure that I own Schwab stock, but I am not being compensated by them or Vanguard for using them in my examples.

Photo by vadim kaipov on Unsplash